THE WORD

The word. It is a potent instrument of transcendence, channeling energies beyond human comprehension, while simultaneously holding a mirror up for the world to reflect on its triumphant spirit of love, as well as its tragic penchant for self-destruction. Centuries before they were first conveyed as written adaptation, the oral word was the essential method of communication, and as civilization evolved it became a determinant factor in evoking emotions that would inspire and motivate the global community, in means both ill and illuminate, through history’s tumultuous arc.

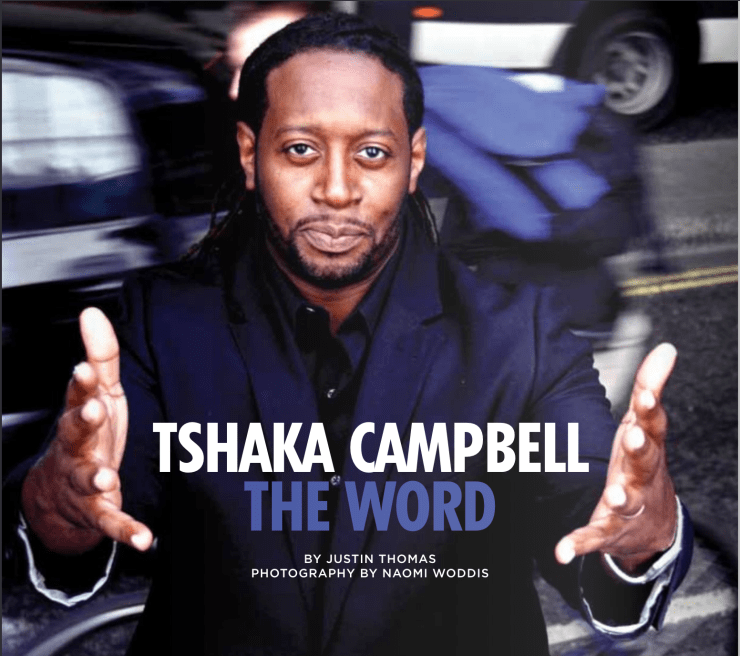

Tshaka Menelik Imhotep is both a student and a purveyor of the spoken word. Referenced largely through the performance circles by his preferred moniker “TarMan Celebrating His Natural Kink”, Tshaka has become one of the more acclaimed and revered artists to emerge from the prodigious pool of spoken word poets within the last decade. An immigrant to the United States at the tender age of ten by way of his native England, Tshaka was raised by his parents in the suburbs of New Jersey, and it was through their early teachings of solidarity that he was educated on the history of his West African roots, his Jamaican lineage, the philosophies of Marcus Garvey and Pan-Africanism, and, especially from his father, the intense power and beauty of language.

“My parents have had a huge influence on me as both a man and as a poet”, Tshaka explains. “Most importantly, I have gotten from them that we are a rich, beautiful and strong people and nothing is gained that is worth keeping without work. I often joke that I am the exact blend of my parents; I get my tenacity, drive and love of language and its power and texture from my dad, but I get my understanding, gentle and communicative nature from my mom. I will be your best friend but your worst enemy. As a poet and as a man, I believe and preach that integrity is your greatest goal and tool. If you are true to your nature, to your cause, yourself and your art, the results of which, although while may not be always the most favorable, are always pure and honest.”

Purity and honesty. It is these two elements of the spoken word at its most intoxicating state that so directly affect the ears and minds of those who listen. The seductive means by which the word can allow one to express his or her joy and pain, remorse and redemption, is enough to elicit a passionate allegiance from even the most jaded audience. Tshaka was smitten by the luring force of poetry at a young age, starting some 15 years ago with a group of peers that he had befriended from Brooklyn, New York. One of these friends had acquired a book of black erotica poetry, and it stimulated the group to start writing poems of their own; twice a month they would hold what came to be known as “Isms at 540”, at 540 Carlton Ave in Brooklyn, and share each other’s writings. Eventually, Tshaka felt the need to express himself outside of the group, and began to attend poetry venues like the Brooklyn Moon, the Nuyorican Poetry Café in Manhattan, and Serengeti Plains in Montclair, New Jersey. He was still developing as a writer, and was taking notes on the various artists he witnessed on his poetry club visits, before he felt comfortable performing his own writings. In 2001, after taking to the stage for the first time to do a reading of one of his poems, he knew he had found his voice.

“I waited in the dimple of a cloud/for a visit from an ancestor,” recites Tshaka in a rendition of his poem “Purpose”, which vividly outlines the trajectory of his journey into becoming, in his own words, a “re-incarnated West African Griot.” “She came to my thoughts dangling from a blade of grass/she had inverted knees and she told tales of walking backwards toward the beginning of journeys…” In his development as a poet, Tshaka has always attested to the significance of oral traditions; in his work, he is venerated for his mesmerizing cadence and is known for summoning the force of Nyamah, which is translated as “the energy of words”. “Oral tradition is as old as human history itself,” Tshaka asserts. “Before written words we had oral presentation. It’s in our history (and) bloodlines. Words change the world, start wars, bring peace, inspire, etc, etc. And if words can do that, and as poets we control and manipulate words, then we can change the world.”

Tshaka also acknowledges the profound influence of his Jamaican ancestry on his ingenious expression, and the lingering spirit of his fore bearers that pervades over all that he creates and all that he is as a representation of his people. “Jamaicans are a truly passionate and expressive people,” exclaims Tshaka, with an exuberance that demonstrates overwhelming pride in his heritage. “That essence is passed down in my genes. I have picked this up through the blood. Jamaicans are a fearless group of individuals and I see that in my work and how I approach the art. In addition, Jamaicans, as with most people of African descent, are rhythmic people. This innate rhythm is woven into my work and enhances in reliability and style. I approach poetry or a poem as a blank canvas where I paint with words, but not only do the words create the look; so does the texture of paint and the thickness of its application. This part of the artistry comes from my Jamaican background – the texture and thickness of my style and delivery.” The relevance of Tshaka’s heredity to the art in which he adeptly crafts is evident in the closing verses of “Purpose”, in which he describes an encounter with a maternal spirit from his lineal past. “‘…This means,’ she said, ‘that you have a reason/a PURPOSE/a reason to open closed eyelids…a reason to map pathways to human intervention/a reason to defy convention’…She blew me a kiss, that landed on my tongue/in the emptiness of her departure, a baby’s heart began to grow in my mouth/it stretched my tongue and began grabbing at my throat, tearing at my vocal cords/it gave form to a female voice/a daughter of speech that grew to puberty within my opinions, and emerged through my lips/in a puff of air, she named herself: Poetry/and sent me a message through the wind that said ‘if you now understand your purpose, say word’/And I said, ‘Word.’”

Throughout the 2000s, Tshaka steadily built his name through the poetry circuits, and would become one of the art form’s most accomplished and respected performers. He has enjoyed the honor of having multiple awards bestowed upon him for excellence in the arena of performance, including becoming a member of the 2004 Nuyorican Poetry National Poetry Slam Team and the 2006 Hollywood National Champion Slam Poetry team. Further accolades came when he received the Grand Champion title at the 2005 San Francisco and 2007 Hollywood Championships. This immense success has enabled him to tour and perform internationally, from the famed Apollo Theater in Harlem, New York to the spoken word venues in cities such as San Francisco. His journey also eventually brought him back to his home country of the United Kingdom, where he currently resides. Tshaka maintains that his excursions across the globe have only served to directly aid in the progression of his art. “Experience is the food that is necessary for artists to sustain themselves,” he attests. “It gives you a more global view of life. I can see how things connect or not, how my narrowed view of things may be supported and or dismantled based on what I have seen in other places. Sort of like, before Malcolm (X)’s pilgrimage; he went to Mecca and saw Muslims with white skin. How could he then continue to preach based on the color of one’s skin after seeing this? But this was not revealed until he traveled and experienced other cultures, other Diasporas, etc. The more I interact with life, the more experiences I have, the more I can reflect that in my work.”

Most recently, the element of inspiration for Tshaka to pause and reflect on through his palette of expression has been his wife and baby daughter. “Having a child and a wife (is) major,” the poet states in a moment of subtle humility. “Your life is not yours anymore –it’s bigger. Your actions affect not just you. Decisions and the ways by which I process those decisions have changed drastically. That’s it in a nutshell – nothing is the same as it was. I can’t get up and travel to wherever to do a show anymore without planning, but I also get to come home from a long working day and see my baby’s smile and hug my wife.” When asked how his wife and child have impacted the content of his writings, he had this to say: “My work/art haven’t changed so much yet—that I can tell at least. I do see that I am writing more about women and varied situations of abuse that are afflicted on them, but not sure if that just a timing thing or triggered by the fact that I have a little girl. I am sure it’s coming though.”

To be certain, what Tshaka can absolutely be sure of is his brilliant star as one of spoken word’s foremost and promising talents continuing its ascendance into the uncharted realms of possibility. In 2006, his preeminence as a performance artist firmly established, Tshaka released his debut CD of performance pieces entitled One to global praise; this resounding reception was followed three years later by his sophomore collection, Bloodlines. He has also ventured into publishing entries of his lyrical prose with the books TarMan, a collection of poems, and Muted Whispers, which contains various selections of short stories.

As poet societies from San Francisco to London anticipate the next phase in Tshaka’s enduring metamorphosis, the poet himself is content to allow his purpose to flow from the eternal guidance and wisdom of the great storytellers that color his people’s narrative. The urgency that one hears when listening to Tshaka recite one of his poems underscores how essential the art of language has become in anchoring the world he has created for himself. “Spoken word is a unique vehicle by which you can induce a number of emotions and reaction when done right – and sometimes all at the same time,” he confides. “You can enlighten and inspire, you can arouse and anger, you can make people laugh or have them reflect on their actions. It also works on the poet them self; often I find it’s the only way to get through an issue or to expel demons that I have running rampant in my head. It’s like breathing for me.”

Word.

Article by Justin Thomas

THE LINGERING EFFECTS OF SLAVERY ON WOMEN OF COLOR

The traditional mainstream studies of colonialism and slavery and its impact on African-American women has long been overlooked (or blatantly ignored) by historians and scholars. The fact of the matter is that history, no matter which time period or subject matter is being addressed, tends to leave out the unique perspective of women and the impact of events and customs of the studied cultures on their livelihood.

In her article “The Legacy of Slavery: Standards of a New Womanhood”, African-American scholar Angela Davis stresses that, unlike their white counterparts, who were viewed as “nurturing mothers and gentle companions and housekeepers for their husbands” (Davis, 1981:5), black women’s role in this respect was virtually non-existent. The typical female black slave was right out in the fields working alongside the men in the same brutal conditions. The only time black women were shown an ounce of leniency from their white slave-masters was when they were pregnant. The reason for this special treatment was because slave-holders were adamant that the slave population remain plentiful as time went on and generations succeeded each other. To them, the black women was viewed as a “breeder”, no more or no less than a farmer were to the female of his herd of cattle as the breeder of a new batch of livestock.

Unlike their male contemporaries in the field, however, black women who were slaves were often subjected to sexual abuse and other atrocities. “Expediency governed the slave-holders’ posture toward female slaves; when it was profitable to exploit them as if they were men, they were regarded, in effect, as genderless, but when they could be exploited, punished, and repressed in ways suited only for women, they were locked into their exclusively female roles” (Davis, 1981:7).

Often times, the structure of the slave family was impacted by the set-up of the slavery system. Because black women were, at least in terms of expectation when it came to labor, viewed as equals among black male slaves, Black men were not viewed as “family head” or the “stronger sex” in the slave family unit. The resulting insecurities and undermining of confidence in male slaves would have an indirect impact on their female partners. It would later be argued in the stereotypical rhetoric of such documents as the Moynihan report, that the result of this lack of male dominance within the African-American family was a deterioration of family structure as a whole, and would lead to the break-down of stability within Black families in succeeding generations. Lee Rainwater, a “liberal” supporter of the Moynihan report, went as far as to say that slavery had “destroyed the black family. As a result, Black people were allegedly left with the ‘mother-centered family with its emphasis on the primacy of the mother-child relation and only tenuous ties to a man’” (Davis, 1981:13).

Perhaps the most ironic legacy of the slavery system and its impact on African-American women, was that it laid the groundwork for future movements among the female black population that would inspire resistance against oppression. Because they could view themselves as “equals” to their male peers, at least in the work field, and they were subjected to such ruthless abuse and exploitation, it would stir passions that would result in Black women asserting their equality. This equality would not be limited to the confines of the male/female relationship within the slave family, but also in other aspects of their life within the slavery system. As Angela Davis points out, “one of the greatest ironies of the slave system” was “in subjecting women to the most ruthless exploitation conceivable, exploitation which knew no sex distinctions, the groundwork was created not only for Black women to assert their equality through social relations, but also to express it through their acts of resistance” (Davis, 1981:23).

The most evil and heartless form of oppression used against Black women was that of rape. Slave-holders used the humiliation of rape as a two-sided coin, or as a means to “kill two birds with one stone”. On one hand, it could be utilized as a method to undermine a slave women’s will to rebel and resist their mistreatment, while at the same time make their slave men feel helpless and powerless, therefore demoralizing them as well from inciting any acts of defiance. “Slave-owners encouraged the terroristic use of rape in order to put Black women in their place. If Black women had achieved a sense of their own strength and a strong urge to resist, then violent sexual assaults –so the slaveholders might have reasoned- would remind the women of their essential and inalterable femaleness” (Davis, 1981:24). Fate would demonstrate how these racist and arrogant assumptions would backfire on the unsuspecting slave-holding classes.

– Justin Thomas

TARGETING CHILDREN FOR PROFIT

Imagine you are walking down the enticing halls of your typical landscape of consumption – the local shopping mall. You are perched on one of several benches upholstered in the middle of the walkway; as you sit and take in the various brand name stores and their respective advertisements and products, the site of a young couple pushing a baby stroller yanks your eyes away from the hypnotic lure of these outlets. The two potential shoppers are an interracial couple, and they each look as though they cannot be older than their early twenties. The bundle of joy tucked away in the carriage is asleep, unaware of its parents’ quest to contribute to the mall’s buzzing consumer machine. As they pass you by without acknowledgement, as if you are a construction or sculpture of some kind, the couple make their way into a Foot Locker. They nitpick at items that appeal to them, but abandon purchasing any once they glance at the price tag. As you watch them, keenly but discreetly, from outside the store, they push the baby carriage into the Kid’s Foot Locker directly next door. Moving into the outlet as to get a better glance at the couple’s shopping methods, you can vaguely make out the conversation between the two young parents. Holding a pair of pint-sized Nike Air Jordan’s, the boyfriend laments, “Nah, these are corny. Jordan’s went out when I was still in high school. Ain’t no way in hell is lil’ man gonna be rockin’ those.” “He’s a baby, Kyle…” responds his girlfriend. “I know,” Kyle continues, “even more important. Start ‘em off right, break ‘em in now, don’t have him be wearin’ that wack sh–.” Therein lay a primary source of today’s child consumer culture.

Since the year 1990, the market for kids (particularly those in the age bracket of between four and twelve), has tripled in earnings. (Cook, Dan–“Kiddie Capitalism” P. 3) That means that in the last decade and a half, the commodification of youth culture has grown significantly faster and larger than its gradual ascension through the previous several decades. What is the cause of this explosion? The reasons as to why in today’s franchise-obsessed society there is a 5 billion dollar name-brand children’s market are varying and often confusing, but there seems to be little to refute the fact that there are three crucial contributors to this ever swelling “epidemic”: the manufacturer, the media, and the parent. The manufacturer is a center-point in the corporate packaging of youth culture; they produce the product, they control the prices at which each item is to be sold, and they vigorously market them to an audience that is often frothing at the mouth for a new style, trend, or fashion sense to devour into its collective consciousness. The other culprit of this system is the media; in some ways their influence is more potent than the manufacturers, in that they translate, through images and rhetoric, the fickle and constantly changing tendencies of the clothing industry. The clothing manufacturers usually use the media climate as a barometer for which styles are profitable, and as the media abandons a previously “hip” trend, the clothing industry follows suit. What may be hot one month (or even one week, in the most extreme cases), probably won’t be in the next, and the media dictates and encourages the consumption of these items while they are bankable commodities, only to discard them at the drop of a dime as soon as a new trend eclipses them. And finally, there is the parent, who is arguably the most important factor, for it is they alone who make the final decision as to whether to buy into the relentless barrage of trends and allow their child to mimick and/or emulate them. More often times than not, they wind up giving in to social pressure, because to not do so would be “risking their child becoming an outcast on the playground.” (Cook, Dan-“Kidde Capitalism” P.3) This reality for contemporary parents is a far cry from parents of yesterday, who dressed their children in a way that would be conservative, respectable, and consistent with the status quo, which at that time was no where near as dominated by the influence of popular culture. Today, to the glee of some and the chagrin of others, popular culture is the status quo, and one’s social standing is judged by whether they choose to buy into the hype or not. As stated in The Consumer Society Reader, “in the culture industry…having ceased to be anything but style, it reveals the latter’s secret: obedience to the social hierarchy.” (P. 11) This revelation non-withstanding, the question now remains as to how this “social hierarchy” relates to the children’s clothing industry; who are the players, and who are the pawns? Only by studying the history of the three aforementioned factors and their relation to the current phenomenon of a name brand-saturated children’s market can one come to even fathom how we have reached the current state of exploitation of “miniature” fashion.

The origins of children’s clothing consumer culture can be traced back to the early 20th century. Prior to the opening decades of that century, children as a demographic in consumer culture was basically non-existent, especially in the clothing industry. One would actually be able to find children’s clothing-wear in the same departments with adult items, for it was (accurately) presumed that it was primarily the mothers of the household who would do the shopping and tend to a child’s needs, and deciding which clothes the child would wear was no exception. The official dawn of the children’s clothing market as its own separate entity, away from the adult outlets, came with the nineteen teens, when the first trade journal of the children’s wear industry was published (The Infants’ Department, 1917), and the financer of that monthly journal, an entrepreneur from Chicago with the prophetic name of George Earnshaw (emphasis on the Earn in his last name), convinced his local department store management that children’s clothing and furnishings should have their own separate department, to make purchasing items easier for mothers. The first edition of the Infant’s Department journal even offered a reward to whichever reader/subscriber could best answer the question printed next to an image of a Caucasian, middle-class women: “How can you make this mother your consumer?” (Cook, Daniel Thomas-The Commodification of Childhood: The Children’s Clothing Industry and the Rise of the Child Consumer P. 42) That question reflected the basic premise by which early child clothing industries operated around – that the mother of these children was their prime target to be advertising to, because children had not yet entered the equation as being viable influences on what was desirable within the consumer market.

All of this changed with the 1930s, and the realization of a previously untapped source: the existence of a youth culture. The emergence of several prominent child stars in that decade, most notably one Shirley Temple, led to a recognition of this ignored demographic, and of course what was to follow was an eventual exploitation of this group of impressionable youth. Temple has been particularly credited to have been a catalyst that spearheaded the children’s clothing market craze that erupted in the Thirties;

as stated in his book The Commodification of Childhood, sociologist Daniel Cook points out that by having her own retail line of clothing that emulated her stage wardrobe (this wardrobe being tailored to her toddler-size frame at the time), Shirley Temple opened the door for “toddler-size style” to become a wildly popular new merchandising category. The extreme success of Temple-style dresses and accessories also proved to the clothing industry that there need not be a limit to how young children should be in order for you to successfully market to them. Temple, along with her peer group of fellow trailblazers in Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland, established the importance of linking the idols of a particular youth culture to sell a related product. By the 1950’s and into the Sixties, with the ascension of post-World War II baby boomers into the youth culture market place, profits within the industry exploded. This can be accommodated to three reasons: for one, the baby boomer generation was the inheritor of a prosperous post-war economy, and having their own money to spend (as opposed to taking money from their parents), they exercised their muscle in dictating what was and wasn’t fashionable. The youth revolt of that era did much to change the sound, look, and style of contemporary America. Secondly, starting in the 1950’s, new literature by the likes of G. Stanley Hall and other sociologists administered an in depth understanding to the complexities of peer groups and peer influences, and gave birth to radical new theories on adolescence that enabled the clothing companies to devise a more direct approach towards marketing their product to youthful consumers. Sales merchants began creating “teen fashion boards” to attract greater numbers of teens to their stores, and departments began to actually hire teenage employees to sell to people of their own age group, a first in the history of the children’s clothing industry. (Cook, P.87) And finally, there was the advent of television. Aside from its various other wide ranging influences on modern day contemporary culture, all industries (and the children’s clothing market was not excluded from this) now had a way of depicting actual moving images advertising their product and instantly beaming them into millions of households simultaneously. The target audience of the developing baby boomers, with their newfound sense of independence and easy access to funds, were eager to spend this money, especially on items that would boost their position of relevance or popularity amongst their peers. Television ads and commercials provided all the motivation these kids needed to get up, go out, and consume. As quoted from George Ritzer’s book Enchanting A Disenchanted World, “Young people now have much more money and play a much larger role in family decisions about consumption, with the result that many of the new means of consumption cater to them directly…” (P. 28)

This scenario continues to play out to a new generation of consumers, only that the children being targeted today are much younger, the methods of advertising are more aggressive and exploitive, and the means by which companies can sell images of their product have been given a tremendous boost with the creation of the World Wide Web and Internet. These web pages for the respective clothing labels “mimic the way we flip through a catalog, and, like a catalog, they suggest a universe of infinite choice…every screen we click on acts as a node of connections to more products that we’re likely to buy.” (Zukin, Sharon-Point Of Purchase, P. 236) Or, to relate that statement to this essay, more products that we are likely to buy for our children? The ascension of this technology to its current state as the dominant means of communication has occurred only over the last decade; can that be a possible way of explaining how the children’s clothing industry has been able to triple in earnings in a less-than 20 year-span? “I think the Internet and the access to so many things that we couldn’t tap into before, has given all areas of commerce a huge advantage when it comes to the sales market,” says Richard, a manager at the “Children’s Place” clothing store in the White Plains Galleria Mall. “The basic ways in which they advertise to us hasn’t changed, but the means by how they are able to do that have definitely changed with online being so big now.” When asked whether any of that means anything when it comes down to the consumer, particularly parents, Richard had this to say: “Again, basic things about shopping and consuming don’t change, they just might be tweaked slightly depending on the times we live in, or by the way we were raised. For example, you were saying mothers used to always do the shopping for their kids; well, it’s the same today. It just might be different because back in the day they might have shopped alone for kids’ clothes, but we almost never see that today. Parents, mostly mothers, ‘cause we don’t get too many fathers coming in here with their children, would rather bring the kids along with them so they can get their opinion on items they are about to buy.” What Richard is pointing out is in pre-children’s market society, mothers would have the last say in what their children would wear. The “seen only when spoke to” mantra that carried over from nineteenth century society dictated that kids had no say in how they were to be presented. Today, however, the pendulum seems to have flipped, for now mothers don’t like to spend money on clothes unless they get feedback from the children themselves. Today’s parents know what it is like to come of age in an environment dominated by pressure from peers and from the media; as Dan Cook states in his article “Kiddie Capitalism”, they themselves are “the living legacies of commodified childhoods gone by”. (P.4) Growing up in a similar means during their own youth, they understand, unlike those early twentieth century parents, that kids feel like they have their own identity and sensibility, and they now have the power to choose which items of clothing they feel will best represent them at the time. “Parents drag their children into the shop and make suggestions as to which clothes the children may want to buy,” Richard continues. “Often, the child (or children) will walk off and point out their own preferences, because they do not want to buy into a look or style that their mother seems to favor; they want to have their own separate identity. The mother then almost always gives in just for the sake of getting out of the store, but not before asking ‘Do you like this? Are you gonna wear it? Are you sure this is the color you want?’ and so on.”

Many assert that giving children a choice when it comes to shopping for clothes is healthy, that it allows them to experience early on the process of consumption and the methods by which you eventually discover your own identity. “The children’s market works because it lives off of deeply-held beliefs about self expression and freedom of choice”, states Cook (“Kiddie Capitalism, P.8), and there are many that agree. However, there is an undercurrent of concern from skeptics who feel that giving children too much free reign when it comes to making choices about their appearance will render them to growing into adults who do not abide by or acknowledge the disciplines of dressing to suit to status quo. Others point out that if all the children want to do is emulate their favorite pop star or sports idol, they are not finding their own identities, but merely morphing into carbon copies of those pop culture icons, thus rendering their born identities to become obsolete in the face of someone else’s image.

The counterpoint to these opinions can be addressed when the question is asked: “What happens when a child’s identity is lost under the veil of their parent’s image?” The flip side of children being free to emulate their idols is when they are modeled in the likeness of their mother or father, and their parents’ individual styles. Young-Ai Heller lives in New York and has worked in the clothing industry for about three years; her current job is at a clothing department in downtown Manhattan that specializes in clothes for infants through sixteen year-olds. Julia Roberts has come in to shop there, and Britney Spears recently called and asked to reserve the store for a day to shop for her baby. Young-Ai says that, from her everyday experience, she witnesses first-hand some of the absurd fashions that parents model on their children. For one, there are “Robeez”, a line of leather (no, that’s not a typo – leather) socks for infants that is currently one of the hottest items in the store. Parents apparently have their babies wear these leather “Robeez” through their infant stage, until they begin to walk, and then of course having the children wear leather socks is “no longer practical”. Another priceless gem that Young-Ai sees parents modeling on their kids are one-piece tops for infants that are part of a line celebrating the legendary punk rock venue CBGB’s. Thirty years after this club nurtured the punk revolution and shook up the establishment, it is now customary at this children’s shop to see parents and/or nannies outfitting babies in shirts with the imagery of such bands as the Ramones, Talking Heads, and Blondie, among others. “Parents feel like their children are another image of themselves”, Young-Ai explains. “Maybe they didn’t have these various clothing options when they were young, and it’s as much fun, if not more fun, for them to now dress their kids in a way that reflects their particular tastes as it is for them to fashion themselves.” When asked about how much of a child’s identity is made up of something concocted through media or through parental influence, she responds “We all live vicariously through the styles and images that are presented to us through mass culture. The difference between children and adults is that, hopefully by the time you are an adult you already have a pretty good idea of who you are, whereas kids are constantly searching for that; maybe trying on different clothes or styles is a way of figuring that out. But the media shouldn’t shove it down their throats that if they don’t look or dress in a particular way, then they are not normal.”

Normal. It’s a word of sparse relevance when discussing the strange and often appalling ways in which the youth are objectified and exploited through mass culture in the name of profits and big business. However, as unsettling as this industry may sometimes seem, the truth of the matter is that there is always going to be a new demographic of children who are coming of age and searching for that image that will, at least for a time, appease their desire to feel a sense of identity that is foreign from that of their parents. As long as there is a media to market this sensibility back to them, the chain of consumerism between the youth and the clothing industry will continue to grow and expand into realms that were previously unforeseen.

– Justin Thomas

THE COST OF GLOBALIZATION

Globalization is the process by which the experience of everyday life is becoming more and more standardized throughout the world. Prices, products, wages, rates of interest, and profits become the same almost everywhere, and this is achieved increasingly through the utilization of technology. This process is performed on varying levels across the board, and the economic and social ramifications of globalization can have both positive and negative effects on human civilization.

To begin with the less heady effects, the positive impact of globalization can be seen in how it has made the process of economic exchange and other factors of modern life faster and more efficient, and thereby (seemingly) more convenient for the general consumer and for society at large. On the economical front for example, where as trade amongst countries used to take weeks or months for a shipment to travel from exporting country to importing country (this would be in the centuries of using boats or ships to cross the seas), today in traveling by plane, a product can reach its destination in a matter of hours, or in the most extreme cases, days (a whole day to wait for a shipment-can you feel the impatience already?). Globalization generally operates as a world system, or transcontinental system, as stated in the text Conformity and Conflict; a transcontinental system “consists of companies and patterns of exchange that transcend national borders.”(Conformity and Conflict, Chapter 9, p. 341) This can be referred to as the “McDonaldization” of the world market, which alludes to the fact that the global economy and system of producing goods and services has become homogenized. This certainly would be beneficial to maximizing profits of any particular world conglomerate, and for those who run these massive companies in the context of the capitalism, the impact of globalization has been nothing short of a financial miracle.

Producers are not the only ones in this equation which benefit from globalization. The consumer, too, has been aided in many ways by the advent of new technologies and new means of attaining a desired product. During the twentieth century, the world was linked in a way which it had never before, with the invention and widespread use of first the radio, and later television. Media became much more pervasive in how we viewed each other and the world outside of our own communities simultaneously, and shrank the globe in terms of how we all became connected through the media’s exposure of different societies and cultures. In the instance of popular culture, many influential styles or movements from the West, such as motion pictures or musical expressions such as jazz, rock and roll, and hip-hop, have traveled far beyond their places of origin in the United States to profoundly influence other nations and other cultures around the world. Without technologies like record or CD players, radio and television, these hallmarks would most likely have remained a phenomena of American society. In the last ten to fifteen years especially, the field of communications has been revolutionized by digital technologies, particularly with the expansion of the use of cell phones and the Internet. Globalization has been aided by these tools of communication, because it gives corporations another vehicle by which they can market their product on a massive scale, and it also makes the process of buying these products faster and easier for the consumer, therefore making their lives less stressful and more convenient.

George Ritzer’s article “The McDonald’s System” attempts to deconstruct the reasons as to why this system is so enticing and attractive; he offers four dimensions that should be credited to the success of what he termed “McDonaldization”. For one, this system offers efficiency; the McDonald’s system, which in many respects should be accepted as a synonym for globalization, “proffers the best available means of getting us from a state of being hungry to a state of being full.” (Ritzer, p. 260) In other words, this system serves up the most efficient way to give the consumer what they want in the least amount of time; when you pull up to a drive through at any fast food restaurant, you want your meal within minutes. For example, today, with the use of the World Wide Web, you do not have to worry about the tiresome and often time-consuming ritual of traveling to a mall to individually shop from store to store to find clothes. Now you can shop for these items online, purchase them online, and have them delivered to your home within a reasonably short period of time. This is called instant gratification, and in a modern day society immersed in the patterns of globalization, the consumer believes that they are entitled to this kind of immediate service. Ritzer’s second dimension to apply to the dominance of the McDonald’s system is that goods and services are quantified and calculated, or that quantity has become the equivalent to, if not more important than, quality. In what seems like ancient times (it was really less than a century ago), it was not uncommon to purchase an item that was specifically hand-made; now, with the use of the assembly line system and machine prowess replacing human labor, the quality of such products has decreased, but more of them can be produced and at a much faster rate. The third minister to globalization is the importance of time; in a rapid-paced society where everyone is always on the go, time becomes a crucial factor which determines how and why people consume. Finally, Ritzer concludes that control is exerted over those who engage in McDonaldization, and yet most do not protest this controlled environment because “people have come to prefer a world in which there are no surprises.” (Ritzer, p. 261)

No surprises, and no cultural diversity. The downside of globalization is evident in many cases, as outlined in Ritzer’s article, that the sovereignty of cultures outside of the fundamentals of big business are placed into jeopardy. Fallout from this global market explosion often leaves societies that do not easily assimilate into the capitalist ideology in economic and social chaos. One example of a people’s way of life being destroyed by the effects of globalization is found in the film The Grapes of Wrath, where the ownership of one’s own land, even if it has been passed down through generations, becomes susceptible to being “repossessed” by the government. This is a prime reason why in modern societies it is becoming less commonplace for people to practice subsistence, or to control their respective societies based on adaptability. Before globalization entered the picture, there were two types of economic exchange in relation to subsistence. One was called reciprocity, where exchanges of goods would be made among family groups or within kinship relations. There were three ways in which the practice of reciprocity was broken down; there was 1) generalized reciprocity, which was based on the assumption that an immediate return was not expected, 2) balanced reciprocity, in which the material value was viewed as being just as important as the social value of any goods, and 3) negative reciprocity, where one would expect to receive something in exchange for nothing. All of these aforementioned aspects to the process of trading goods for services are irrelevant now, where an economic exchange method known as redistribution has risen to prominence. Redistribution is the exchange of goods and services through some kind of centralized entity, and this would be more aligned with the economic patterns of globalization because of its controlled environment. Redistribution is a part of the new “market economy”, where there is no longer a need for reciprocal obligation; it is all about the money, which is bolstered by the fact that all of the products being sold via this method have also been set by a world market. With such rigid industrialization and global standardization having been instated, how is it possible for cultures outside of these institutions to maintain subsistence? The “modernization theory” has studied how different modern societies have developed in order to participate in the modern economy, but it isn’t always so easy, especially when the template being set for most others to follow is being dictated by one country (the United States), when it exerts its power and influence over other nations; this is known as the world systems theory. As stated in the Conformity and Conflict text, “companies and patterns of exchange…may evade control by individual governments” (Culture and Conformity, Chapter 9, pp. 341-342) and that “local people can easily find themselves both motivated by and at the mercy of world markets.” (Conformity and Conflict, Chapter 9, p. 342)

As George Ritzer stated in his “McDonald’s System” article, there are pitfalls to this system of rationality, and that there is actually such a thing as the “irrationality of rationality”. (Ritzer, p. 262) Although the implementation of a globalized market economy might maximize the amount of exposure (and therefore profit) a corporation may receive, there are drastic tolls that this can have on any particular society or group of people that are forced to work within the confines of this system. As outlined in the film No Logo, it has been well documented about how multinationals have established factories around the world, mostly in underdeveloped nations, to take full advantage of the inhabitants of these regions and offer them jobs for the smallest amount of pay. The companies view this as a way save money for themselves because they are utilizing cheap labor, and yet they justify this process because they feel they are giving employment opportunities to those who otherwise would have no way of supporting themselves. These arrogant assumptions disregard the fact that the people who work in these factories, many of them who are children, work under the poorest conditions for long and brutal hours, and in many respects this becomes a form of slave labor. Corporate brands from Nike to Coca-Cola are all guilty of this blatant exploitation; the reverberating impact of the labor industry in these countries can have a detrimental impact on a people’s family structure and stability.

The article “Women in the Global Factory” perfectly describes how people, specifically women, can be manipulated and abused at the hands of corporate entities. It states that following World War II, when foreign product began to directly compete with American made products and labor costs at home steadily rose, the U.S. concocted a response; “they began to outsource their labor intensive production tasks to ‘export processing zones’ located in Third World countries. There, labor was largely provided by women because women could be paid less and were more accepting of authority.” (Fuentes and Ehrenreich, p. 164). Another article which illustrates the fallout from globalization is “Cocaine and the Economic Deterioration of Bolivia”, found in the Conformity and Conflict text. The practice of subsistence has been “eroded”, because families who once farmed on their own lands now have been deprived of the use of that land. The men of these families are then forced to find alternated ways to feed and support their families, and many of them have had to leave their homes entirely to look for work elsewhere. The absence of the father from any given family, especially in the rural societies of places such as Bolivia, can permanently scar the structure of not only the family, but their extended communities. The article describes how many of these families turned to growing cocaine to earn a better living than they would growing papayas, sugarcane, cotton, grain, or any of the other traditional cash crops. Many of their fields and cocaine factories were in turn raided by the same governments (the United States and countries throughout Europe) who not only placed the globalizing mentality onto their cultures which robbed them of their means to practice subsistence (in turn forced the heads of the household to abandon their families), but were also the very countries which were supporting the drug trade because their respective nations had the greatest demand for the cocaine product. Regardless, many of the women and children who labored on these fields or in these factories were subsequently snatched from villages throughout Bolivia and imprisoned. This is an example of the effects of globalization at its ugliest.

The final argument about how globalization has had a negative impact on the world in terms of culture and society is evident in the decline of individuality. In an environment where there is a McDonald’s arch in probably almost every populated area around the globe, where is there room for unique perspectives and ideas? The predictability of a world dominated by the effects of globalization has meant that there is a general detachment from ourselves and from each other, and the relentless bombardment of images which are attempting to entice us into consuming during every minute of everyday has isolated or alienated many people from the realities of modern society. They question why we have come to a point where interpersonal relations no longer matter, and why we for all intents and purposes can not return to this simpler, freer time. As George Ritzer pointed out, this will not occur because “the increase in the number of people, the acceleration in technological change, the increasing pace of life—all this and more make it impossible to go back to a non-rationalized world, if it ever existed, of home cooked meals, traditional restaurant dinners, high quality foods, meals loaded with surprises, and restaurants populated only by workers free to fully express their creativity.” (Ritzer, p. 263) He was alluding to how fast food entities like McDonald’s have impacted the ways in which we consume food, but he may as well be referencing how all the above can also apply into every other facet of modern life, whether it be how we work, how we enjoy entertainment, and everything else that consists with living in a globalized society. As seen in the documentary film No Logo, some people, desperate to escape, have made pilgrimages to Celebration, Florida, which is a throwback to the more simplistic times of the 1950s, where emphasis on family and interpersonal values and morals romantically trumps attempts by the media and the corporate world to dictate how we should conduct out lives. It is a novel idea, and on outset one can understand why those weary with our McDonaldized communities would be drawn to such a place. There is only one problem: Celebration was created and is sponsored by the Walt Disney Corporation, which entails that this “paradise” is itself a McDonaldized entity. Everything that pertains to this development is in direct reference to the Disney company; you won’t see any McDonalds or Coca-Cola ads anywhere, but everyone from your dentist to your chiropractor is probably a representative of the worldwide Disney conglomerate. In actuality, living in the retreat of Celebration should demonstrate that there really is no escape from the pervasive influences of globalization.

To summarize, globalization has both made the world a more convenient place to live and a more treacherous place to live. The defining factor of this dichotomy is more than likely based on where one resides. If you live in America, by most assumptions, you will be living somewhat comfortably with the use of your iPhone, driving your motor vehicle down to the McDonald’s drive-thru on your way to work at some kind of multinational company. Life is convenient enough, with little worry about how you are going to maintain a roof over your head or where you will be able to find your next meal. If you are a child slaving away in the cocaine fields of Bolivia, not only is your place of residence and ability to obtain a meal on shaky grounds, but you also do not know if in at any minute these fields will be raided by drug enforcement, and in an instant your livelihood, as well as your own freedom, will be taken from you. If anything, the ascendance of globalization in the last half century has sharply increased the disproportions between these two worlds, and if there are any wrongs in the practice of this globalized world market that need to be corrected, it is this reality.

– Justin Thomas